Child perceptions of safety vary across agencies

To download this information, click here.

Note: The number of children who responded to the question “I feel safe here” is indicated under the column for each agency.

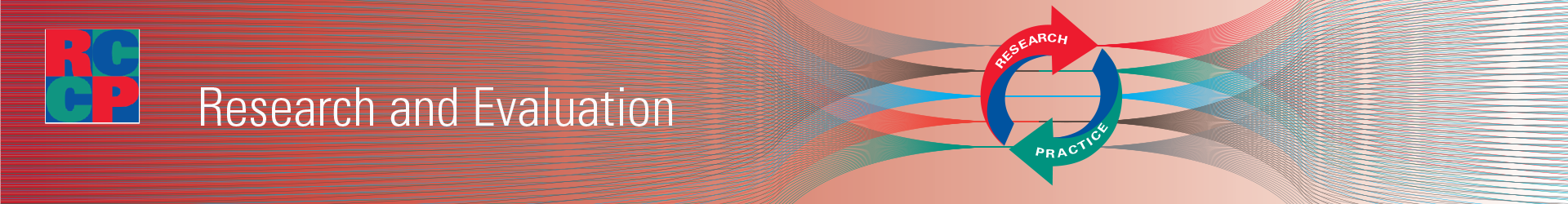

This study examined perceptions of safety in 29 North American residential care agencies. In two different surveys, which we call Dataset 1 and Dataset 2, children were asked how often “I feel safe here.” For Dataset 1, 352 children from 13 agencies responded, and for Dataset 2, 363 from 16 agencies responded.

The results varied substantially across the agencies in both datasets. As shown in the figure, the percent of children who said “Never” or “Rarely” ranged from as low as 0% to as high as 57%. In fact, there were two agencies with 50% or more of children responding “Never” or “Rarely.” There were only seven agencies where 75% or more of children responded “Usually” or “Always” feeling safe.

Sellers, D. E., Smith, E. G., Izzo, C. V., McCabe, L. A., & Nunno, M. A. (2020). Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of adult-child relationships. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 37(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2020.1712576

Child perceptions of safety increase as quality of relationships with staff increase

To download this information, click here.

Note: Linear mixed models were used to estimate the association between safety and the quality of relationships with staff after controlling for agency and child characteristics.

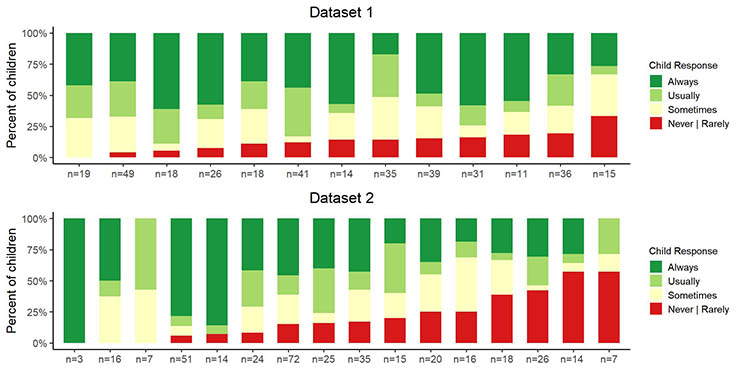

This study examined perceptions of safety in 29 North American residential care agencies. In two different surveys, which we call Dataset 1 and Dataset 2, children and youth were asked how often “I feel safe here.” For Dataset 1, 352 young people from 13 agencies responded, and for Dataset 2, 363 from 16 agencies responded.

In both datasets, the higher the child’s perception of the quality of the relationship with staff, the more likely the child was to report feeling safe even when controlling for available child and agency characteristics. That is, perceived safety increased 0.86 (standard error = .09, p-value = .000) and 0.76 (standard error = .07, p = .000) for each one-unit increase in the Youth Perception of Relationship Quality measure (YPRQ) in Datasets 1 and 2, respectively. The YPRQ measure is designed to capture the child’s experience of the types of interactions that are key components of high-quality, trauma-informed, therapeutic relationships (e.g., Sensitivity to the child’s experience and needs, Availability/ Responsiveness, etc.). The important perspective for staff is their attunement to the child’s needs and experience of the relationship and their ability to adapt and address those needs, thus ensuring that the child’s experience of the relationship is positive and supportive and facilitates feeling safe.

Sellers, D. E., Smith, E. G., Izzo, C. V., McCabe, L. A., & Nunno, M. A. (2020). Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of adult-child relationships. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 37(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2020.1712576

Staff perceptions of child safety are higher than those reported by children

To download this information, click here.

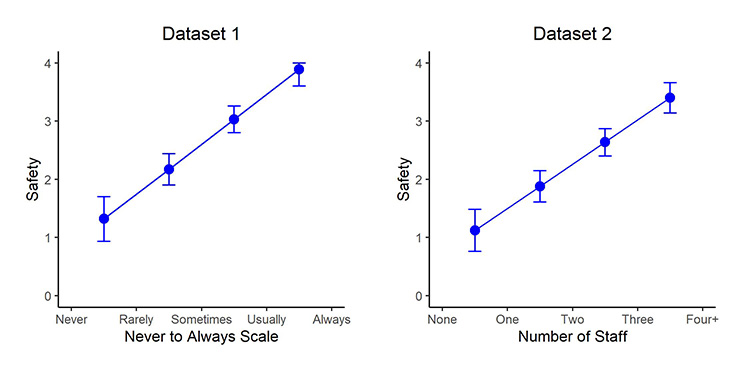

In seven agencies, the staff and children completed surveys concurrently, so staff and child perceptions of child safety could be compared. Child report is the percent of children who responded “Always” or “Usually” to the question “I feel safe here.” Staff were asked two questions: “Children feel physically safe here” and “Children feel emotionally safe here.” The graph shows the percent of staff who responded “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” to each question.

In general, staff perceptions of children feeling physically safe differed very little from their perceptions of children feeling emotionally safe, with only two agencies, B and F, having differences greater than 5 percentage points. However, agencies varied in the degree to which staff agreed or strongly agreed that children felt safe, ranging from nearly 100% in two agencies (C and G) to about 75% in two agencies (E and F).

In most agencies, staff’s perceptions did not align well with those of the children. The percentages were similar in only two of the agencies, F and G, while in one agency, Agency A, the difference was about 40 percentage points.

Sellers, D. E., Smith, E. G., Izzo, C. V., McCabe, L. A., & Nunno, M. A. (2020). Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of adult-child relationships. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 37(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2020.1712576

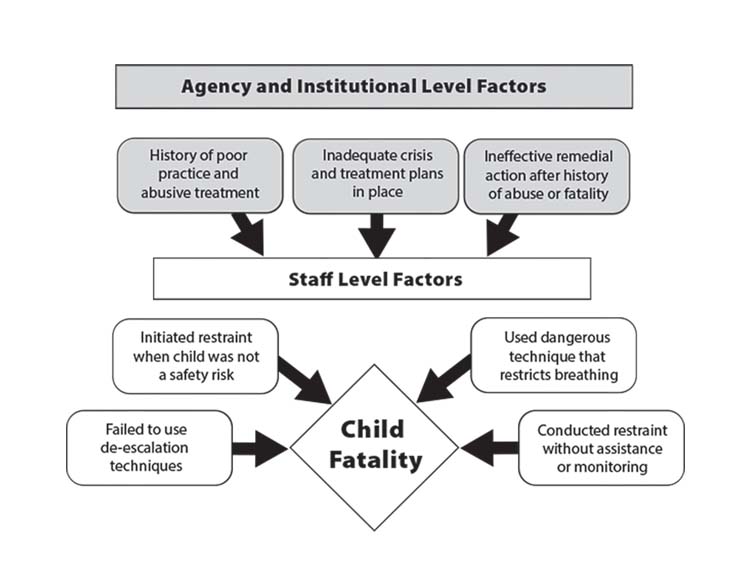

Restraint factors attributed to a confluence of medical, psychological, and organizational factors

To download this information, click here.

Examination of 79 U.S. child fatalities that occurred due to restraint practices in out-of-home care over a 26-year period (1993-2018) provides a picture of the children who died and how the fatalities occurred. The composite case presented below represents features of restraint fatality incidents reviewed for this study. A composite is reported in order to efficiently illustrate the confluence of interacting factors typically seen, while also protecting the identity of children and their caregivers. Note that any of these factors are within an agency’s power to resolve.

A shirt Plymouth loved was missing from her closet. Angered, she ran to her friend to accuse her of taking it. She was stopped and escorted back to her room by a staff member. Agitated, she went into her closet to prove to him it was gone and she retrieved a small object. Staff demanded to know what was in her hand; she refused to comply. A supervisor, hearing the disturbance, shouted “settle her down in there it’s time for dinner.” Responding, the caregiver initiated a single-person restraint in the closet, lost her balance, and fell on Plymouth who landed face-up. Staff remained on Plymouth’s torso to maintain control until she was non-responsive. Plymouth died from asphyxiation. Her death was the 4th restraint-related fatality within the organization over the past 8 years. Days prior to Plymouth’s death, the state’s regulatory agency placed the center on probation because of “excessive” restraints, the frequent use of medication for control, and the lack of individualized treatment and crisis plans. Two years prior, leadership and staff were cited for abuse when they “encouraged” the girls to wrestle with one another for food.

Nunno, M. A., McCabe, L. A., Izzo, C. V., Smith, E. G., Sellers, D. E., & Holden, M. J. (2021). A 26-year study of restraint fatalities among children and adolescents in the united states: A failure of organizational structures and processes. Child & Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09646-w

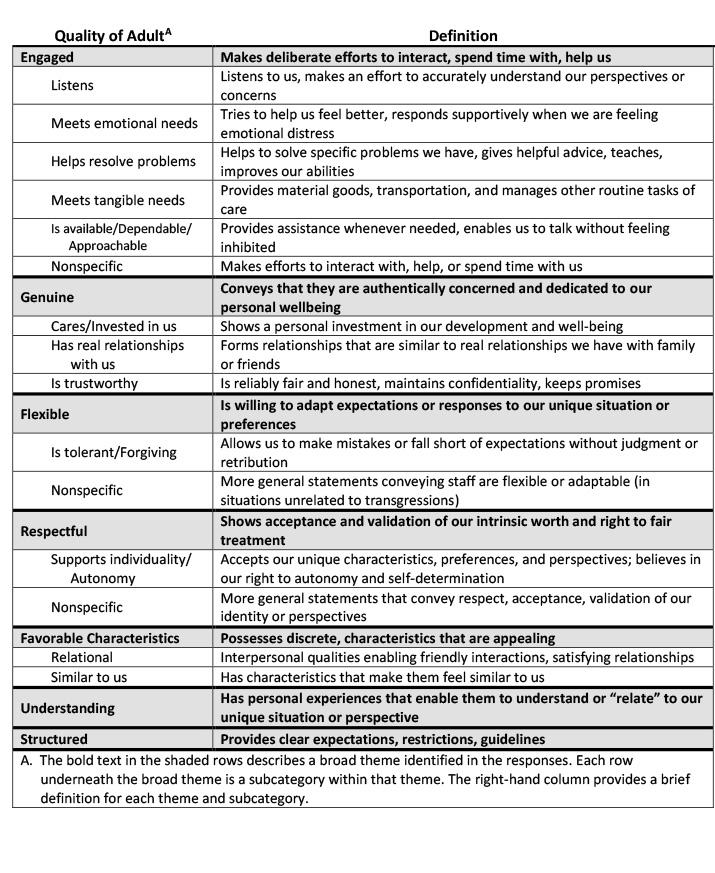

Qualities of residential youth care workers that are valued by youth

To download this information, click here.

Qualitative analyses of 597 responses to an open-ended survey question about the characteristics of their favorite staff member from children and youth living in 16 residential care agencies in two states in the southeast yielded seven broad categories of responses. As indicated in the table below, five of these categories included several subcategories. These findings provide insight into how youth appraise and describe their relationships with key adults and may help residential care agencies’ efforts to maximize their fit with the needs, preferences, and best interests of the youth they serve.

Izzo, C. V., Aumand, B. N., Cash, B. M., McCabe, L. A., Holden, M. J., & Bhattacharjee, M. (2014). Exploration of the youth-adult relationship in residential care. Small glimpses from a large sample of youth. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare, 15(1–2), 10–23. https://ugp.rug.nl/IJCFW/article/view/37854

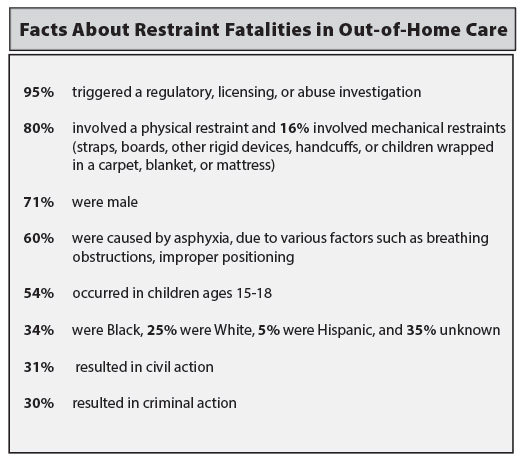

Facts about restraint fatalities in out-of-home care

To download this information, click here.

A study of 79 U.S. child fatalities that occurred due to restraint practices in out-of-home care over a 26-year period (1993-2018) focused on (1) who the children were that died due to physical restraint and (2) how they died. RCCP researchers employed Internet searches of publicly available sources from reputable journalism outlets, advocacy groups, activists, and governmental and non-governmental agencies to discover and compile information about restraint-related fatalities of children and youth up to 18 years of age.

Of the 79 fatalities documented in the study:

Nunno, M. A., McCabe, L. A., Izzo, C. V., Smith, E. G., Sellers, D. E., & Holden, M. J. (2021). A 26-year study of restraint fatalities among children and adolescents in the united states: A failure of organizational structures and processes. Child & Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09646-w

Heresniak, R., Ruberti, M., Turnbull, A. & Nunno, M. (February 2022). QuickTRIP: Translating Research Into Practice: What we know about children who have died from physical restraint in the U.S. Ithaca, NY: RCCP, Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research (BCTR), College of Human Ecology, Cornell University.

The RCCP routinely collects data from the staff who work at and the children served by organizations who implement our programs. In some cases, administrative data from these organizations is also available. In addition, funded evaluation efforts often yield data that lends itself to purposes beyond the particular evaluation. Whenever possible, we use the data from these sources to contribute new knowledge to relevant fields.

Child Perceptions of Their Own Safety:

Increased as quality relationships with staff increased

Staff Perceptions of Child Safety:

Were higher than those reported by children